(I wrote this article about Herschel Williams, Sr. in September, 1997. He was 79 years old at that time.)

“God be with thee, glad some Ocean! How gladly greet I thee once more! Ships and waves, and ceaseless motion, and men rejoicing on thy shore.” Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1801

I was recently looking out of my upstairs window over the village of Avon and thinking of what one of my cousins said to his sister when we were at their father’s viewing, the night before the funeral. He told her, “That’s just his body, he’s gone.” He said this to his sister to comfort her that their father’s soul had left its temporary dwelling, his body, and gone on to a better place.

Sometimes I wonder if the soul of Avon has gone, too. The enclave of the old village of of Kinnakeet (Avon) is still here, but does it still have its soul? It was a sad thought.

But then I met with some real Kinnakeeters, and I know all is not lost. There are some old timers still left, and some of their grandchildren too, who embody the qualities of a Kinnakeeter: self-reliant and faithful, hearty people who could stand hard times and the greater test of good times.

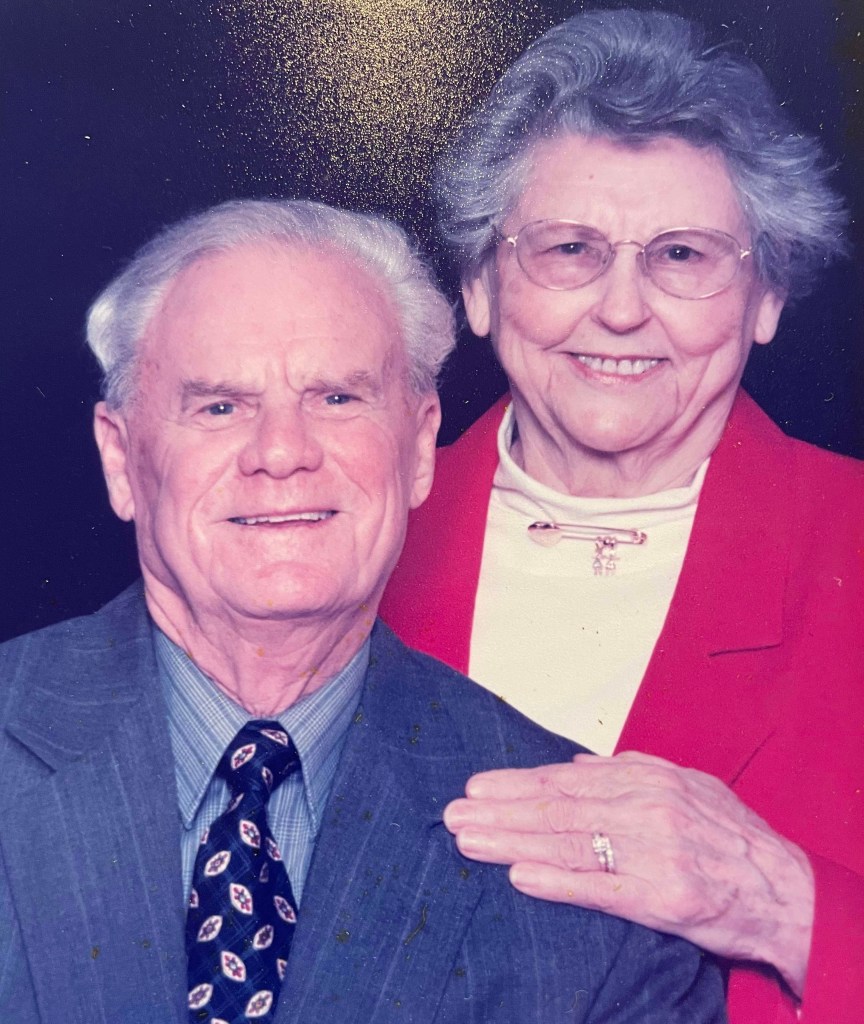

Herschel Williams Sr. is one of those Kinnakeeters.

He and his wife, Leona, live most of the time in Elizabeth City now, but still have their home on a back road of the village. It’s a large white house and it was full of delicious smells the day I stopped by. Mrs. Williams hugged me and welcomed me to their home, confessing she had burned the potatoes. They still smelled good to me. And then instead of the usual questions and answers of an interview, Mr. Williams took me to a different place in time as he told me about his father, Andrew Williams. He had written a poem about him and his life as a net fisherman. He recited by memory this rhyming reflection on a man’s work as his life, on a man’s family as his love, and on a man’s faith as his anchor.

Mr. Williams read his other poems to me as well. They are unpretentious poems of an unpretentious life. Net fishing, duck hunting, and one about the establishment of the village church in 1881. He read his short story, “The Story of the Frogs”. He gave me the booklet his daughter had typed up for him, called “These Things I Remember”. It’s an all too short memoir of his childhood days in Kinnakeet.

The village of Avon was an isolated place when Mr. Williams was born in January of 1918. There was no indoor plumbing. Villagers drew their water from rain barrels or from a well usually some distance from their home. A wood or coal stove was used for cooking and heating. Herschel’s father, Andrew Williams, fished his nets, oystered in the winter, and sometimes served as a hunting guide for “those rich Yankees”. Tailor nets were set in April. Tailor is what the fishermen called bluefish.

He would set his nets in a place known as bog channel for about two months until the tailors headed north for the summer. Then “ hungry June” came, a month when there weren’t many fish to be caught.

Set netting would begin in July. Andrew Williams would leave home after lunch (known as dinner) taking leftovers, usually fish, with him for his evening meal. He used a sail skiff as his fishing boat. A sail skiff had a main sail and a jib. Ballast, consisting of two burlap bags filled with sand, was used to balance the skiff so it wouldn’t turn over.

Once at his fishing spot Williams would set about 30 nets, net about 30 yards long. The nets were anchored with eight feet long stakes. It was hard work, especially in the wind, sticking those stakes down far enough to hold the nets in place.

Williams was through with work by sunset and then it was time to eat supper. Herschal Williams’ memoir records, “I used to hear him say that everything my mother fixed, regardless of what it was, always tasted good out on the sound”.

By the time he had eaten his supper the sun had disappeared in the west. He would wait until what he referred to as “daylight down” to begin fishing those nets. Daylight down was when it was no longer day and night time began.

Williams would go to the windward end of the nets and take out the fish while the skiff drifted. When he was through, he would lie down on an old bed quilt that he had spread on a platform that was built in the bow and rest a short while until daybreak. Then he would pull up his nets and go to the fish house to sell his fish. Once the fish were sold, he had to hang up each net on shore to clean them and let them dry. He had time for a short nap before lunch, then another trip out into the sound. Set netting lasted through November. By October the nets could be left overnight to be fished each morning. Nets were set from Monday through Saturday. No work was done on Sunday.

Oystering would begin in November. Andrew Williams shared ownership of a two masted sailboat,”The Two Sisters” with Henderson Miller. The boat had a cabin to eat and sleep in and was 65 feet long. Williams and Miller went across the Pamlico Sound to Long Shoal to harvest oysters. They used oyster tongs and a small oyster dredge to harvest a boatload of oysters in just a few days. The oysters were taken to Elizabeth City to sell for a price of 40-50 cents a bushel. They sometimes traded their oysters for corn, peanuts, or pork sausage at Weeksville, which is south of Elizabeth City.

The men stayed away oystering for about two weeks. Then they went home for a few days. Many men, including Williams, developed arthritis at an early age from oystering in the bitter winds of winter. Oyster season lasted until early spring.

During the winter the men sometimes set “jack nets”. These were nets with larger mesh than the nets used in the summer. The nets were set in the deep channels to catch jack fish, a very bony fish, and also speckled trout.

Williams provided food for his family with vegetables from his garden as well as fish from the sound. In the late summer and early fall he would salt a barrel of fish for the times he would be away oystering in the winter. He also loved to hunt; the family ate wild fowl in the winter and shore birds in the summer. Mrs. Williams canned vegetables for the winter. The family kept chickens as well for eggs and meat, and a cow named “Lovie” for milk.

Crabs were not eaten at that time and were considered a nuisance by fishermen because they played havoc with their nets. The crabs would also eat the fish in the nets if the nets were left out for any length of time.

All too soon my time at the Williams household was over. I felt so rude when I turned down Mrs. Williams offer to stay for lunch and I was hungry from the smells of her cooking. But as a mother of two small children time is short. I had to pick the girls up and take them home. Time is so precious and goes so quickly. There is never enough time to just visit and talk. I’m so thankful for this job; it sends me out seeking the treasures that are found in learning people’s stories, and I am never disappointed.

(H.P. Williams Sr. Was born on January 27,1918 in Avon. He died at the age of 99 on March 29, 2017. He served in the Civilian Conservation Corps at Camp Beaufort for 2 years, then in the Navy for 21 years. His last job before retirement was with a local phone company for 21 years.

His wife, Leona Meekins Williams, was born on March 14, 1921. She died at the age of 102 on March 17, 2023. They were married for 73 years. She was a nurse in Elizabeth City. At the time of Herschel William’s death, the couple had 2 daughters, 2 sons, 11 grandchildren, 15 great grandchildren, and 2 great-great grandchildren.

Andrew Peele Williams died at age 70 on April 21, 1951. His wife preceded him in death a month earlier. They had 2 sons and 4 daughters.

Poem by Herschel P Williams called

“My Dad”

In the village of Avon on a January morn,

God saw fit for me to be born.

And the day that I came into the world

My mom and pop were glad I wasn’t a girl

For they already had four females and my dad

Wanted someone that could weather out a gale.

For he was a fisherman most of his life

And he needed some help to support these girls and his wife.

Though God had blessed them with a son

Who had helped dad with the fishing some

But he was fixing to leave home,

Let go out in the world and be on his own.

So shortly after I became a lad of 10

My dad said son it’s time for you to begin

To learn to fish and give me a hand

So tonight we leave from this point of land.

He got his boat and we put it in gear. It was

Summertime and our time of the year.

And we headed that about boat out to a slough

Where the fish would be feeding the whole night through.

We fished those nets time and again

And ever so often dad sang a hymn.

For that was his kind of life

Trying to make a living for we kids and his wife.

Though he never made very much dough

He caught a lot of fish but the prices were low.

But he was happy just the same for he put his trust in Jesus’s name.

Then one day against his will

He had to put away the nets because he became ill.

And I guess it was the day he really died

for when he stopped fishing he lost his pride.

Now he’s up in heaven with some big fishermen

Fellows like St. Peter and Andrew

who lived long before him

And I bet they talk about the fish they caught,

up there where no battles are fought.

And someday when my work is done,

I plan to join them beyond the setting sun.

And I’ll listen to all those fishermen,

who followed Jesus to the end.

Thank you, Rhonda. You’re writing style is so vivid I felt like I was either in Herschel’s home or in a skiff, oystering in February. I’ll take Herschel’s living room. Love ya.Hal

Yahoo Mail: Search, Organize, Conquer

LikeLike